In this article we will discuss about National Income:- 1. Concept of National Income 2. Circular Flow of National Income 3. Major Types of Production 4. Measurement 5. Major Classes 6. Expenditure Approach 7. National Income as the Generic Term 8. Statistics 9. Interpreting Measures 10. National Income (Output) and Per Capita Income 11. Measurement Problems and Others.

One of the most important concepts in all economic systems is the national income. Technically, it is called the gross national product (GNP). Economic growth is symptomized by an upward movement in GN P as the key variable. So GNP measures the economic performance. A more reliable indicator of the performance of the economy is per capital income.

It may be recalled that macroeconomics is the study of those forces, economic and physiological, that determine the four key macro variables, aggregate employment, production, real income, and the price level.

In the words of P. Samuelson, “The concept of national income is indispensable preparation for tackling the great issues of unemployment, inflation, and growth.” Modern economists are, however, more concerned with the quality of life than with the material growth. And it is in this context that the concept of net economic welfare (NEW) has been developed.

2. Circular Flow of National Income:

The foundation-stone of macroeconomics is the circular flow of national income. In fact, the whole of macroeconomics is built on the simple concept of circular flow. This simple circular flow model now provides the starting point of our study.

We first try to identify the major types of production in the economy. Then we study how the circular flow of income can be measured. We shall observe that there are three ways of arriving at an estimate of national income. The three methods give us identical results.

Any discrepancy among the three measures is largely due to statistical error (also known as rounding off error). We finally discuss a number of conceptual and practical problems associated with the measurement of national income.

A consumer is an individual who purchases goods for his (her) own consumption. This term is used in microeconomics. In macroeconomics we use a broader term, viz., the household.

According to R.G. Lipsey, “A household refers to all people who live under the same roof and who make joint financial decisions about, among other things, the purchase and consumption of goods.” In macroeconomics we use this term ‘household’ to describe the basic purchasing unit for consumption goods.

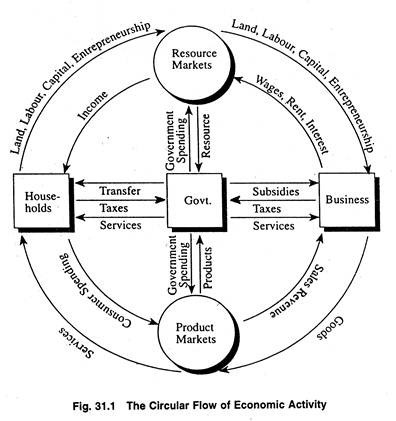

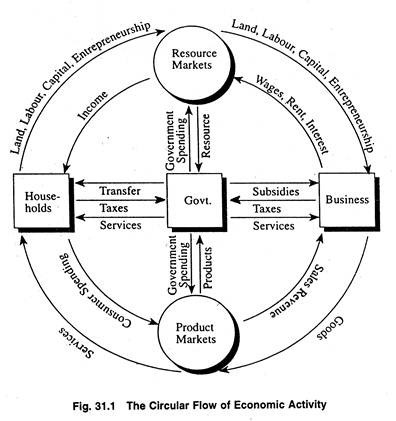

Money, goods, and factor services (also called economic resources or inputs) flow through the economy in a circular manner, as depicted in Fig. 31.1. There are three major transacts (government, business, and households) and two basic kinds of markets (resource markets and product markets).

The participants in free enterprise markets exchange the resources that business and government need in order to operate: land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurial talent.

For example a business buys land, labour, and capital from resource markets and pays rents, wages, and interest for these resources. Households contribute land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurial talent to resource markets in exchange for income.

In product markets, households spend money for consumer goods and services, and government provide these goods and services, such as law court, or police protection to households and businesses. In turn, it receives taxes from them.

It also uses the markets to purchase resources and products (e.g., medicines for hospitals and the services of school teachers) paying for them from its tax resources. So, business, government, and households are interdependent.

Each of these three groups help create and maintain economic activity in a process that continues over and over again, as shown in Fig. 31.1. From this pattern, practicing managers learn that they must keep abreast of changes in households and government, as well as the activities of other businesses.

3. Major Types of Production in National Income:

The circular flow diagram identified two basic units of an economy, viz. producers and consumers. Recall that production is any activity directed to the satisfaction of other people’s want though exchange.

In a modern economy total production is divided into three main categories, viz. consumption goods (like bread, butter, clothing, etc.), investment (or capital) goods like coal, electricity , etc., and services such as (postal service, railway service, banking service, insurance service, etc.)

Such goods include the output of all goods and services for consumption by households. Thus along with various commodities we include all types of economic services that are rendered to satisfy human wants (such as haircuts, legal advice, medical care, etc.).

We may now note the following three points about consumption goods and services:

1. Omission of Second-Hand Goods:

Consumption goods include only currently produced goods and services such as new cars produced by PAL in 1994. But we exclude the purchase of second hand (old cars) from the economy’s current production because it is just a transfer of ownership of an existing asset.

However, any commission to be paid to second hand car dealers is a part of current production because the car dealer is providing a useful service (which is paid for). His commission will be treated as part of the economy’s current production and will be reported as a current contribution to national product.

2. Reporting at the Time of Production:

The second point to note is that consumer goods and services are included in the measurement of production when they are produced, not when they are consumed.

For example a 1975 model car that lasted 15 years was produced in one year and its service was consumed over the 15 years. In case of perishable goods like vegetables or services like haircuts, there is hardly any difference between the time .of production and consumption.

3. Treatment of Housing:

Households buy houses. But in national income accounting housing is counted as an investment good and not as consumption good.

In macroeconomics investment is divided into three parts: fixed capital (like plant, equipment and machinery), circulating capital (including stocks of finished goods, any raw materials) and residential housing.

Society’s total investment in an accounting year consists of the following:

(1) The amount of new capital goods,

(2) New additions to circulating capital and

(3) New residential houses constructed over that period.

An economy’s current output of fixed capital includes the following terms:

(1) Currently constructed factory and

(2) Currently produced capital goods (like machines and equipment).

Circulating Capital:

Circulating capital is known as stocks or inventories. In agriculture, corn is treated as circulating capital because corn is required to produce corn. This is why a farmer sets aside a certain portion of his output every year, to be used as seed next year. So the distinction between output and input gets blurred.

But in industry, circulating capital consists of the following three types of stocks:

1. Stocks of Finished Goods:

These are held because production and sales do not always coincide. A publisher, for example, may print 10,000 copies of a textbook. This may be sold over a period of 10 months or one year.

2. Stocks of Semi-Finished Goods or Goods-in- Process:

Such stocks are held as a matter of routine because the same commodity or resource may have to pass through different stages of production before being finally consumed by households and business firms. An example of this is paper.

A publisher has to keep printed paper for some time to be made available in the form of textbooks at the beginning of the academic year. Or an automobile manufacturer like PAL may keep stocks of car chasis to be made available in the form of finished cars when demand arises.

3. Stocks of Raw Materials:

Business firms have also to keep stocks of raw materials like coal, oil, or steel to ensure uninterrupted production of finished goods. A shortage of raw materials may lead to sudden disruption of production. A firm’s current investment in stock is the difference between end- of-year stocks. We say that there has been an accumulation of stocks or positive investment in stocks.

The converse is also true. If, for instance, stocks held at the end of the year are smaller than stocks held at the beginning of the year, stocks are being reduced. In this case, economically useful things produced in the past have not been replaced.

Two related points may be noted in this context. Firstly, the word ‘stock’ is used in a restricted sense, to denote circulating capital. Secondly, in a general sense the term is used to refer to a quantity that does not have a time dimension.

Investment may be gross or net. Gross investment is net investment plus depreciation (or capital consumption allowance). In other words, net investment is gross investment minus depreciation. There is need to provide for depreciation because capital goods wear out through use and have to be replaced. So differently put, total investment = replacement investment + net addition to society’s existing stock of capital.

Government Production:

It is necessary to distinguish between two main types of government expenditure, viz.,

(1) Current expenditure on goods and services or on factors of production and

(2) Transfer expenditure.

The government’s current (exhaustible) expenditure refers to outlay on such things as road building and maintenance, national health, salary of government employees (such as police personnel, lawyers, managers of public sector enterprises, etc.,) and defence. All government current expenditure is included in national output, i.e., they are counted as producing output of goods and services.

The second type of expenditure is called transfer expenditure because it is merely transfer of purchasing power from one group of people to another. This is expenditure on such things as interest on government bonds, unemployment compensation, retirement pensions, etc. In a modern economy, payments are made to certain sections of society at the cost of the tax-payers.

Those who receive such payments (such as the unemployed, the handicapped, the needy families, etc.) do not provide anything to the government in exchange. This is why such payments are called transfer payments. However, because of such payments the modern mixed economy is called by the name ‘welfare state.’

Transfer expenditures do not add anything to current marketable output: they merely transfer purchasing power from tax-payers to the recipients. Therefore such expenditures or payments made by the government are not treated as a part of the government’s current output of goods and services. So in our discussion of national income we confine ourselves to current expenditures.

4. Measurement (Estimation) of National Income:

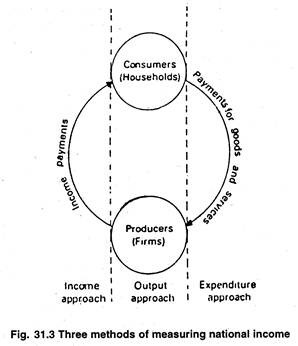

There are three different, but interrelated, ways of measuring a country’s national income or the total market value of a nation’s output, viz., the output method, the income method and the expenditure method. These three methods are illustrated in the following circular flow diagram (Fig. 33.3). We may now discuss in detail how national output or income is measured by using each of the three methods (approaches).

1. The Output (or product) Method:

The first approach is to add up the market values of all output produced by business firms. In order to estimate total output of society we have to add up the money values of different types of production such as tonnes of steel, barrels of oil, number of motorcars, etc.

We have to express the market value of every commodity (or service) in terms of money because the units of measurement are different for different commodities. This approach measures the circular ‘flow by going directly to producers and is illustrated by the middle of the circular flow diagram presented in Fig. 31.3.

When we use this method we face a problem. While measuring the value of each producer’s output, we face the problem of double (multiple) counting. In a modern economy, characterised by division of labour and specialization, the output of one industry (such as iron one) becomes the input of another industry (such as steel).

In other words, the same commodity may pass through different stages of production or the output of almost every commodity occurs over a series of stages, each stage being carried out by separate firms. Thus teaspoons may be made by one firm, from stainless steel provided by a second firm, which, in its turn, used iron ore provided by a third firm, and transported by a fourth.

If we add up the market value of the sales (output) of all the four firms, viz., the iron ore mining firm, the steel plant, the transport firm and the spoon manufacturer, we would surely get a total well in excess of the value of final output of teaspoons.

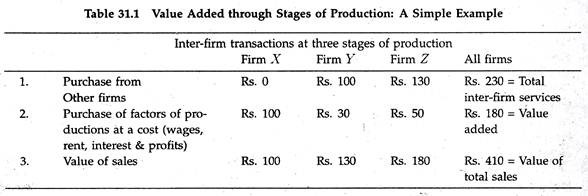

The problem of double counting is avoided by using the value added concept, i.e., by defining the output of each firm as its value added.

The term value added is the difference between the output of a firm and the costs of raw materials and other inputs (intermediate goods) it purchased from other firms. In other words, the term refers to the amount added to the value of the production (under consideration) by the firm’s own activities.

According to the product method (also known as the value added method) the national output of a country is the sum of the values added by all the firms in the economy. This concept is illustrated in Table 31.1. From this table it is clear that production passes though three stages, started by the basic producer X, through the intermediate firm, Y, and ending up in the producer of the final product, Z.

Here firm X produces the basic material (iron ore) valued at Rs. 100 (provided it has not purchased any input from other firms). Firm Y purchases these new materials, valued at Rs. 100, and produces semi-finished (intermediate) goods (finished steel) which it sells for Rs. 130.

Firm Z purchases these semi-manufactured goods for Rs. 130 and converts them into a finished product, such as spoons. It then sells these spoons for Rs. 180.

It thus adds value of Rs. 50. Thus there are two ways of finding out the value of finished goods (Rs. 180):

(a) either by counting the sales of firm Z or

(b) by taking the sum of the values added by each firm at three different stages (of this example).

This value is less than the Rs. 410 that we arrive at by adding up the market value of the commodities sold by each firm.

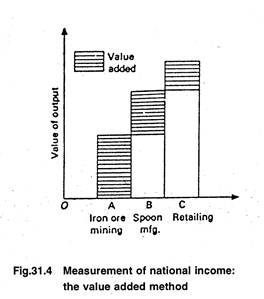

In Fig. 31.4, we illustrate the concept of ‘value added’. Here the value of the annual output of the steel industry is represented by the height of Column A. This forms the input of the spoon industry (Col. B), which in turn forms the input of retailing (Col. C). To add A, B, and C together would involve double counting.

For instance, the value of steel output would be added three times instead of only once. So care must be taken to add together only the values added at each stage of production. In Fig. 31.4 these are shown by the shaded areas.

If these shaded areas are added together, they equal the height of the final column. An alternative method of measuring output, therefore, is to take the value of the final product alone, ignoring the value of the intermediate products.

The above illustration enables us to distinguish between two types of goods: intermediate goods and final goods. The former are goods and services that are sold by one firm to be used as inputs by another firm. The latter are the end-product of economic activity i.e., they are the economy’s output.

The final output includes all consumption and investment (capital) goods as also goods and services produced by the government. The contribution of each firm to final output is measured by its value added.

Thus national output or gross national product is the sum total of all final goods produced in the economy in an accounting year. This is why the output (product) method of measuring national income is also known as the value added method.

Market Price:

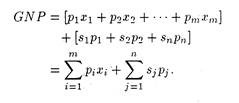

National output is measured at market prices. So the total of gross national product (GNP) is simply the sum of annual flow of final goods and services:

price of apples (p1) x number of apples (x1 )+ price of bread (p2) x number of bread (x2), etc. plus the money values (pj) of services (Sj):

We use market prices as weights in evaluating and adding up diverse physical commodities and services. And here the definition of J.R. Hicks is quite relevant.

In his language:

“National income is a collection of goods and services reduced to a common basis by being measured in term of money.”

Now market prices are relevant variables here inasmuch as they are reflectors of the relative desirability of diverse goods and services. To use the language of Samuelson:

“The net national product or ‘national income evaluated at market prices’ …. is …. the total money value of the flow of final products of the community.”

The Income Method:

According to the income method, total output can be looked at in terms of the incomes generated in the process of producing the output. It measures the flow around the left hand part of the circular flow diagram (Fig. 31.3).

Not only accounting convention but sheer common sense also tell us that all market value that is produced must belong to someone. Thus all output produced automatically generates income for the factors that take part in the production process, plus an amount that goes to the government.

The sum-total of all these is the total value of this output. Thus whatever production occurs in an economy, some income is simultaneously (automatically) generated in the process. However, the income may be paid out only after selling the output.

5. Major Classes of National Incomes:

Usually five major classes of income are included in national income.

These are the following:

These are called income from employment since these represent that part of the value of production which is attributed to labour. This is perhaps the major component of a country’s national income. This includes gross salary and compensation before deduction of income tax, social security and provident fund contributions.

This refers to the incomes of privately and publicly owned producers who sell their outputs in the market: So we have to include trading surpluses of public sector enterprises in national income along with profits and dividends accruing to the private sector.

This refers to depreciation. If we subtract this from gross national product (GNP) we arrive at net national product (NNP).

This is a very small item. It includes incomes of the self-employed persons such as farmers, doctors, lawyers, traders, etc. It also includes income from unincorporated business.

It includes rents received by those owning property let out to others as also what is called ‘inputted rent’ of owner occupied houses (i.e., income from house property). In most countries, a rental value of houses occupied by its owners is imputed to the owner’s income even though no actual rent is paid or received. Let us see why this is so.

When a multi-storied building (consisting of, say, 96 flats) is built, the expenditure incurred on it is a part of the gross profit of the owners of the flats. When a private dwelling house is constructed, the expenditure on it is a part of this year’s investment.

When it is occupied by the owner, say next year, a rental value for the use of the housing facility is imputed and included in the total value of output of goods and services. This imputation of rent to owner-occupied housing is absolutely essential if all housing, whether owner-occupied or rented, is to be treated at par.

Taxes and Subsidies:

In the absence of all types of taxes and subsidies, the market value of all output would be identically equal to the incomes earned by the owners of the land, labour and capital used in the production process. Taxes and subsidies, however, create gap between these two totals. The following example will clarify the point.

Suppose the Government of India provides a subsidy of 50 paisa per kg to the producer of wheat. Now every kg of wheat produced can generate 50 paisa of income to the farmer over and above its market value. Suppose wheat sells for Rs. 4 per kg but there is a subsidy of 50 paisa to producers. Then the factors engaged in producing wheat will earn Rs. 4.50 for every kg produced.

Now we may consider the effect of indirect taxes such as excise duty or sales tax on goods and services produced and consumed: Suppose instead of subsidy, there is a tax of 50 paisa on every kg of wheat sold. While the market value of each kg of wheat produce remains at Rs. 4, the incomes earned by the factors used to produce that wheat will be only Rs. 3.50: the extra 50 paisa will go to the Government as revenue.

So it is clear that in the case of a subsidy, incomes earned by the factors of production (market value of production plus subsidies) exceed the total value of output. On the other hand, in case of an indirect tax, income earned (the. market value of output less taxes collected by the government) fall short of the total market value of output.

Two adjustments:

Because of taxes and subsidies it becomes necessary to make two adjustment when we add up incomes generated by production in order to arrive at the total value of production measured at market prices. Otherwise, NNP and NNI will not be identical. There will be discrepancy between the two.

Tax adjustment:

Firstly we have to add indirect taxes, since these are very much part of the market value of output that does not give rise to factor incomes, i.e., incomes going to land, labour or capital.

Subsidy adjustment:

Secondly, one has to subtract subsidies on goods and services from NNP since these allow incomes to exceed the market value of society’s output.

Net indirect taxes: taxes minus subsidies:

In measuring national income we consider the combined effect of the taxes and subsidies. What is considered is therefore net indirect taxes which is the difference between total indirect taxes and total subsidies. This point is slightly complicated. To avoid confusion we have to be very careful.

Confusion can be avoided if we remember the following two points:

1. If we have all factor incomes and want to get the market value of output, we must add in net indirect taxes.

2. If, on the other hand, we have the market value of total output and want to get factor earnings, we must deduct net indirect taxes.

NNP vs. NNI:

While NNP is the sum of all values added, NNI is the total value of income generated by output. Thus while the output approach measures the nation’s output as the sum of all value added in the economy the income method measures the value of total output at market prices as the sum of all factor incomes generated by the production process.

This is obviously the sum of all wages, interest, profits and rent plus net indirect taxes.

Transfer Income:

While using this method we have to omit any transfer incomes in order to avoid the problem of double counting. Thus the pocket money received by a student from his father is to be excluded. Similarly if you receive a gift from your father who is also a resident of India it is to be excluded from India’s national income.

6. Expenditure Approach in National Income:

The expenditure approach is also known as the total spending approach. When we use this method we arrive at the nation’s total output by adding up the expenditures or outlays needed to purchase all of the final output of the economy. This method measures the flow around the right-hand part of Fig. 31.3.

Three main categories of total spending are the following:

(a) Consumption:

This refers to society’s total expenditure on consumption goods and services in an accounting year and is denoted as C.

(b) Investment:

This refers to the value of the output of capital goods over the year and is denoted by the symbol I.

(c) Government Expenditure:

The current expenditure of the government is included in society’s output. In this context we have to note an important point. When the government spend money to produce goods and services that are sold in the market, they are valued at current market prices.

However, various types of current expenditure of the government are not associated with the production of goods or services that are sold in the market such as public parks, government hospital, roads, highways etc. The value of the output resulting from such expenditure is arrived at by calculating the amount of money spent on them. Hence their valuation is at cost.

While estimating the government’s contribution to national income from the expenditure side, we need only to meet the government’s current expenditure. This is denoted as G. We exclude all transfer expenditure.

A closed economy:

In a closed economy, having no trading relation with the rest of the world, the total value of expenditure (Ec) on society’s output is expressed as:

where Ec is total expenditure in a closed economy. Here investment I includes change in stocks while government expenditure excludes government transfer payments.

An open economy:

However, in the real world no country is self-sufficient. Each country has to import certain things which it cannot produce at all or produce efficiently. Similarly, to pay for such imports it has to export certain things which it can produce efficiently (i.e., at low cost). Therefore a portion of the expenditure in each of the categories (C, I, or G) goes to purchase goods produced in other countries.

For example, total expenditure on oil bought in India includes not only purchases of oil made in India but also purchases of oil produced in other countries and imported to India. The expenditure on imports creates incomes in the producing countries, not in India. Thus, to discover the output produced by the oil industry in India, we must subtract from total expenditure on oil by India, the amount that is spent to import oil.

The same type of consideration applies to all other types of domestic expenditure. Some expenditure on investment goes to buy equipment (such as picture tubes) and materials (such as fertilizers) imported from abroad.

The same argument applies in case of government expenditure. For example, the Ministry of Finance may import a Japanese computer or the State Trading Corporation of India may purchase food grain form abroad in a year of bad crop.

Thus to arrive at national output from the expenditure side, it is necessary to subtract from C + I + G the value of all expenditures on imports which may be expressed by the symbol M.

Exports: Exports (denoted as X) create a similar problem. When Italians, Swedes and Germans buy Indian textiles this is expenditure on Indian production. Thus in order to calculate India’s national output from the expenditure side, we have to add in all expenditures by foreigners on Indian goods (exports).

Net exports:

Thus to estimate national output by expenditure we have to add exports and subtract imports. The difference between the two (X — M) is called balance of trade or net export. So we get:

E0 = C + I + G + (X – M)

where E0, total expenditure in open economy which is the sum of C, I, G and net export (X — M).

In all three approaches the total value of the value of the nation’s output at market prices is the same. This identity of income, output and expenditure may be expressed s follows:

where O is the aggregate output, Y is the income it generates and E is the expenditure incurred to purchase it.

Firstly Y and O are identical in that Y does not measure incomes actually paid out during the course of the year, but instead measures the incomes generated by producing O (plus the amount realised or collected by the government form net indirect taxes.) The identity of Y and O then follows from the conventional accounting practice that the value of all output must accrue to someone.

Thus what is not wages, interest or rent must become either the profits of the producers or must go to the government as indirect taxes. All factor incomes are accounted for by output.

It is because someone must own the value of output (GNP) that has been created or, in other words, the net value of all that has been produced is the joint contribution of all factors. So each factor has to be paid according to its contribution to net output. Thus all factors are to be paid for offering their services.

The money value of all factor incomes is net national income. In other words, the net value of all output produced in an economy is identically equal to the net flow of income generated through the production process in an accounting year. The two have to be identically equal.

Moreover, goods produced and not sold are valued at market prices, and the difference between their value and their cost of production is treated as profit. This is recorded as part of profit income. However, this does not accrue until the goods are actually sold.

The identity of O and E follows from the fact that E measure the expenditure required to produce the nation’s output, which is the same thing as the market value of that output. In arriving at an estimate of total expenditure, the national income accountants add up the amounts of money actually spent to purchase what is sold.

To this must be added the amount that would have to be spent if the output added to stocks had been sold instead, i.e., firms are assumed to have purchased the inventories and to have paid the market price for; them. This establishes the equivalence of E and O.

Thus total output is the same for all three approaches. But the breakdown is different in each case. These three estimates are needed not for the sake of definition but because they serve different purposes. Their breakdown differs.

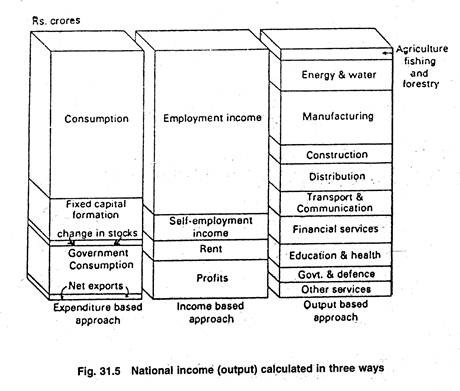

In case of O, it is of industry of origin, such as electricity generation or car production, in case of E, it is by type of expenditure; in the case of Y, it is by type of income, such as wages and salaries, interest, profits and dividends. Figure 31.5 shows the major components of each of the three measures.

7. National Income as the Generic Term:

We have seen that, when properly (correctly) measured, output, income and expenditure are identical.

They yield a single final figure that measures three things at the same time, viz,:

(1) The market value of output,

(2) The incomes earned by producing that output (plus) net indirect taxes and

(3) The expenditure to be made to purchase that output.

The usual term used to refer to this single total is national income and is denoted by the symbol Y. Thus, when we speak of national income, we are referring to the total value of income earned in the country in an accounting year, as well as to the total value of current output, as also to the total value of the expenditure needed to purchase that output.

8. Statistics of National Income:

While measuring national income we come across a series of expenditure measures. Each one gives a somewhat different final figure, and each gives us useful and interesting information.

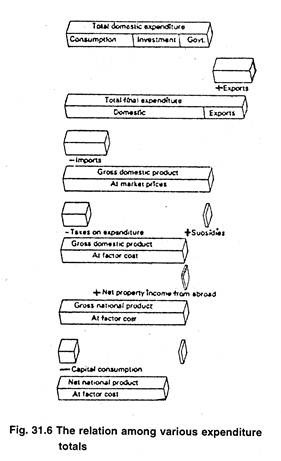

The relation among them is illustrated in Fig. 31.6 and discussed below:

1. Total Domestic Expenditure:

The most important and reliable measure is total domestic expenditure (TDE). It is the foundation of all other expenditure measures. It is defined as the sum of all expenditure on final output that is made within a country irrespective of where the output was produced. TDE = C + I + G.

2. Total Final Expenditure:

The second concept is total final expenditure (TFE) which is expressed as TFE = C + I + G + X

So we add export (X) to TDE to get TFE. Thus TFE is the sum of expenditure on final output incurred within an economy, irrespective both of the country in which goods and services were produced or the country in which they were consumed.

Problem 1:

Suppose indirect taxes are Rs. 35; household disposable income (gross income less direct taxes) is Rs. 5100; government net taxes form households is Rs. 900; consumption spending is Rs. 4600; investment spending is Rs. 500; and government spending is Rs. 935.

Find out GNP. [GNP is found by summing indirect taxes, household disposable income and direct taxes (35 + 5100 + 900), or by summing consumption, investment and government spending (4600 + 500 + 935).The figure is Rs. 6035.]

(a) From the following data for India, establish the amount of domestic output available for Indian purchase, and the total amount of goods and services available for Indian purchases: GNP is Rs. 1000; gross exports equal Rs. 100 while gross imports are Rs. 150.

The amount of domestic output available for Indian purchases is GNP— Exports = Rs. 1000 – Rs. 100 = Rs. 900. The total amount of goods and services available for Indian purchase is Rs. 1050 – the Rs. 900 from domestic production plus the Rs. 150 of imported goods and services.

3. Gross Domestic Product:

This measure is perhaps the most comprehensive of all. This is domestic product (GDP) at market prices. It is arrived at by deducting imports from TFE. This expresses GDP (at market prices) = C + I + G + (X — M).

Thus by subtracting imports from GDP we reduce its value by the amount of expenditure that is directed to purchase goods and services produced in other countries. The convention is to lump exports and imports together into a single (X — M). This is also called net exports.

The GDP at market prices give the value of all final expenditure on goods and services that are produced within the country.

4. GDP at Factor Cost:

The fourth measure is gross domestic product at factor cost. It is a measure of GDP at the cost of the factors used in producing it, and thus of the income received (earned) by those factors. It differs from GDP at market price due to the presence of net indirect taxes.

So there is need to change GDP at market prices, by adding government subsidies to the production or sale of society’s output and by subtracting taxes on production or sale of the social product. Due to subsidies, or negative taxes, factor income exceed the market value of goods sold.

On the other hand due to indirect taxes (or taxes on expenditure) incomes received fall short of the market value of goods sold. It is because some of sale proceeds accrue to the government as revenue.

Thus we get:

GDP (at factor cost) = GDP (at market prices) + subsidies – taxes on expenditure.

5. GN P at Factor Cost:

The fifth measure is GNP at factor cost. This is the sum of all incomes earned by Indian residents in exchange of contributions to current product that takes place anywhere in the world. If your father (who resides in the UK) send an annual remittance of $ 2000 for the maintenance of your family in India, this will be a part of India’s national income.

If we are to arrive at GNP form GDP we have to proceed in two steps. Firstly, we have to add wages, interest, profits and dividends received by Indian citizens from assets that they own overseas. Thus if you receive a dividend income of Rs. 100 from a company based in the USA it will be a part of India’s national income. Such receipts are part of incomes earned by Indian citizens but they are not a part of India’s production.

Secondly, we have to subtract interest, profits and dividends received by foreigners on assets located in India, but owned in other countries, if we want to arrive at income earned by Indian residents.

Although these are a part of India’s production, these are incomes earned, not by India, but by foreign residents. After making these adjustments we arrive at a final figure, called net factor (property) income from abroad.

This is expressed as:

GNP (at factor cost) = GDP (at factor cost) ± net factor income from abroad.

6. NNP at Factor Cost:

The sixth and final measure is net national product (NNP) at factor cost. This is arrived at by subtracting depreciation (or capital consumption allowance) form GNP. Thus NNP is the net flow of output generated in the economy after deducting from GNP an amount necessary to keep intact society’s existing stock of capital.

The NNP measures the maximum amount that could be consumed by the private and government sectors, keeping the economy’s stock of capital unchanged. (In Indian National Account, this is known as net national income).

NNP (at factor Cost) = GNP- depreciation (or capital consumption).

In a similar fashion, if we subtract depreciation form GDP we arrive at NDP. Similarly GNP – C + I + X – M and NNP = C + In + G + X – M. Here I is gross investment and In is net investment. Thus the difference between the two measures is due to the single term, depreciation.

All the six measures are of total output and total income. We may now consider two more measures. The object is to highlight some important parts of national income. So from the physiology of national income we pass on to its anatomy.

Personal Income:

National income accountants also make use of the term personal income. It refers to the gross income of the household sector, whether as factor payment or total outputs, before deduction of personal income tax. It thus excludes incomes received by the corporate sector or by government.

But personal income includes transfer income which is not included in national income. Thus at least three important adjustments are to be made to NNP (at factor cost) to arrive at personal income.

1. Firstly, we have to subtract from NNP all income taxes paid by business (since these are included in the value of output that is not paid to households).

2. Secondly, we have to add to NNP all transfer payments (since these generate incomes for persons that do not arise out of current production).

3. Thirdly, we have to deduct all undistributed business profits (or retained earnings of the corporate sector). It is because these incomes are not paid out to persons. The firms usually retain the funds for their own expansion and diversification.

So national income is not necessarily the sum of all personal incomes.

Personal Disposable Income:

So long we have said nothing about direct taxes such as income taxes. We have only referred to indirect taxes which create a divergence between two measures of NNP, viz, NNP at market price and NNP at factor cost. Now we may see what accounting treatment is given to direct taxes.

Any factor income includes a certain amount of direct tax which is deducted at the source. Thus if we subtract direct (income) taxes form personal income we arrive at personal disposable income. This is what is left to households, after paying taxes and social security contributions, for spending or saving. Thus

where DI is disposable income, Y is NNI,T is income tax paid, C is consumption spending and S is saving.

Disposable incomes (DI) figure tells us what actually gets into our hands, to disposes of as we please. To get the figure we have to subtract from the GNP figure, depreciation, all taxes (direct and indirect), retained earnings of the corporate sector, and then to add transfer payments of welfare or interest -on-national debt type.

The disposable income figure is important because it is this sum that people divide between consumption spending and net personal saving. Of course people also pay interest on loans out of this income. Businessmen keep a close watch on the trend of DI for obvious reasons.

Like DI, personal income (PI) removes depreciation and corporate saving from GNP and adds back all transfer income including subsidies.

The distinction between personal income and disposable income is that the former does not attempt to estimate personal income-tax (which is basically a direct tax). If it excluded all taxes, PI would be identical with DI.]

One of the most important relationship that arises from national income accounting is that between saving and investment. To provide the necessary background to our study of the Keynesian theory of income, determination, it will be useful to show here that, under the accounting rules described above, actual (measured) saving is identically equal to actual (measured) investment.

The basic question here is: what is the basic measure of investment in standard national accounting system? In a simple closed-economy without government, we know that investment (I) is that part of output shown in the circular-flow diagram which is not spent on consumption goods (C).

The next question is: what is the measure of saving? If we assume that in our simple economy without government and foreign trade companies do not save and retain earnings, saving, shown in the lower part of the circular flow diagram, is that part of disposable income, or GDP, which is not spent on C.

In short: I Less C

S = GDP (from the income side) less C

But the two approaches do give the same measure of GDP. Hence we have I = S: the identity between measured saving and investment.

In a more complex economy, total gross national investment (In) will include both gross domestic investment (I) and net foreign investment (X).

But gross saving (5) has to be divided into three broad components:

(1) Household (personal) saving (HS) which originates from disposable incomes;

(2) Gross corporate saving (GCS), which is depreciation plus any earnings retained in the firm; and

(3) Government revenue surplus (GRS), which is the excess of government’s current tax revenue over its current expenditures on goods and services and on transfers.

Now in a four-sector economy the identity of measured national saving and investment, S and In. can be shown in terms of the three components of total S:

In = HS + GCS + GRS = total saving.

In a situation where companies do not save and retain earnings, this identity reduces to

This simply means that domestic investment plus net exports equals personal saving plus the budget surplus.

In fact, we can derive the fundamental identity from the very definitions of GDP. and of saving. The fundamental identity for GDP from the product side is

GDP = C + I + G + X.

Since gross national investment (In) is the sum- total or I and X, we can express the product side of GDP as

Now a breakdown of GDP from the earnings of cost side shows GDP – DI + GCS + Tr-Tp where Tr = tax revenue and Tp = transfer payments.

Since DI = C + HS, we have

GDP = C + (HS + GCS) + (Tr – Tp – G) + G.

Since GRS = Tr – Tp – G, we can cancel G and G to obtain our required saving-investment identity:

In = HS + GCS + GRS.

If we assume that there is no business saving, we can derive a final useful identity. Now we have

The simply means that domestic investment plus net exports equals personal saving plus the budget surplus. The relationships can be summarized in the following words of Paul Samuelson and W.D. Nordhause: “National saving always equals national investment in plant, equipment, and inventories and investment abroad. The sources of saving are personal saving, business earnings and depreciation, and government saving (i.e., the government budget surplus). This identity must hold whether the economy is in tranquil times, is going into depression, or in a wartime boom”.

In a two-sector (household and business) model, suppose households receive the following compensation from business: wages Rs. 520, interest Rs. 30, rent Rs. 10, profits Rs. 80; consumption spending is Rs. 550 and business investment is Rs. 90. Find

(a) The market value of output and household saving,

(b) What is the relationship of saving and investment?

(a) The market value of final output is Rs. 640, found by summing household compensation (wages of Rs. 520 + interest of Rs. 30 + rent of Rs. 10 + profits of Rs. 80), or by summing consumption and investment Rs. (550 + 90). Household saving is Rs. 90, found by subtracting consumption spending of Rs. 550 from the Rs. 640 received by households.

(b) Both saving and investment equal Rs. 90. This relationship always holds true in a two-sector model, since saving leakages must always equal spending injections.

(a) Find GNP and NNP for a private sector model from the following data: consumption, Rs. 850; gross investment, Rs. 100; depreciation, Rs. 40; household compensation (wages + rent + interest + profit), Rs. 910. (b) Prove that for a private sector model depreciation D plus household saving S equals gross investment Ig: (2) household saving equals net investment In.

(a) GNP is Rs. 950 of this private sector model, found by summing household compensation (Rs. 910) and depreciation (Rs. 40) or by summing consumption (Rs. 850) and gross investment (Rs. 100). NNP is Rs. 910 the sum of household compensation or the sum of consumption (Rs. 850) and net investment (Rs. 60)

(b) In a private sector model, GNP = C + Ig, GNP = C + S + D. and Ig = In + D. Thus, Ig = GNP-C and S = GNP-C-D or S+D = GNP – C. Since GNP – C equals Ig as well as S + D, Ig = S + D. Subtracting D from both sides of Ig = S + D we get Ig – D = S and In = S since by definition Ig – D = In.

From the following data, find (a) national income,

(d) personal income,

(e) personal disposable income and

(f) personal saving.

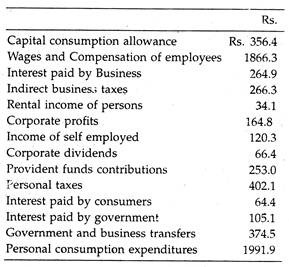

(a) National income = compensation of employees + business interest payments + rental income of persons + corporate profits + proprietors’ income. National income = Rs. 1866.3 + Rs. 264.9 + Rs. 34.1 + Rs. 164.8 + Rs. 120.3 = Rs. 2450.4.

(b) NNP = national income + indirect taxes = Rs. 2450.4 + Rs. 2663 = Rs. 2716.7

(c) GNP = NNP + capital consumption allowance = Rs. 2716.7 + Rs. 356.4 = 3073.1.

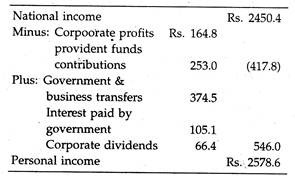

(d) Personal income:

(e) Personal disposable income = Personal income – personal taxes = Rs. 2578.6 – 402.1 = Rs. 2176.5.

(f) Personal saving = Personal disposable income – (personal consumption expenditures + interest paid by consumers)

Personal saving = Rs. 2176.5 – (Rs. 1991.9 + Rs. 64.4) = Rs. 120.2.

9. Interpreting Measures in National Income:

The information provided by measures of national income can prove to be very useful for various purposes. However, if these measures are not properly and carefully interpreted these can mislead us too often.

Moreover, each specialized measure gives us a different type of information. Hence each may be most useful for studying a particular problem. We may start with two variations of NNP. Each one gives us some useful information.

Real vs. Money National Product:

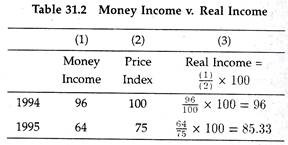

So far we have been concerned with money value of national product and we used money prices in the market to combine various goods like apples, oranges, haircuts, plastic surgery to a single figure. But this nominal measure precludes any sensible comparative analysis.

If the 1995 price level turns out to be much higher than 1994 level, with the same amount of physical quantities of goods and services, we will arrive at much higher 1991 nominal national product figure. So, measurement by the rubber yardstick is undesirable.

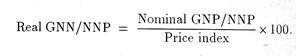

What we need is a real GNP/NNP measure. To arrive at a real figure, we have to deflate the money national product figure by the index number of price.

The procedure is simply this:

This is also known as national income at constant prices. See table 31.2.

Thus it is because of inflation (deflation) that we draw a distinction between two measures of national income: national income at current price and national income at constant price. Even India’s national figures are expressed at two set of prices.

Price vs. quantity change:

When there is a change in money income, we know that the market value of total output has changed. This may be due to change in either, or both, the quantities and prices of final goods. When there is a change in real income, we know that this is due to changes in the quantity of final output (with the prices at which output are valued remaining unchanged).

10. National Income (Output) and Per Capita Income:

For some purposes, particularly for studying changes in standards of living over time in a country, or for making international comparisons of income and living standards we need a measure of per capita income or output per head. It is obtained by dividing national income or NNP by the size of the population. We often compare living standards on the basis of per capita disposable income at constant prices.

This measure enables us to compare living standards of a single country over time as also make an international comparison, if disposable incomes are all measured in one currency, such as US dollars (or in terms of prices prevailing in one country such as the UK).

Sometimes we divide GNP by the number of persons employed to arrive at GNP per employed person. We also divide GNP by the total number of hours worked to arrive at output per hour of labour input. This is called GN P per hour worked. Since the last two measures give us estimate of overall labour productivity they are a test of economic efficiency rather than well-being.

11. Measurement Problems in National Income:

We have already referred to some theoretical (conceptual) problems that arise when we seek to measure a country’s national income in three different but interrelated ways. Some practical problems also crop up when we attempt to measure national income.

The following three problems appear to be the most important in this context:

1. Classification:

The first problem is how to classify those items which are suppose to be a part of national income. While expenditure on all durable goods are treated as consumption goods, expenditure on housing is normally classified as investment expenditure. This is done arbitrarily as it is the convention in most countries.

Similarly paint used by a painter to do his art work is a raw material. Sup- Dose he is left with some surplus paint with which by paints his own house. In that case it is a consumption (final) good.

There are practical problems regarding coverage of items in national income (expenditure). Let us consider, for example, interest on debt. In general, interest on private sector debt is included in national income but interest on public debt is not. The latter is an example of transfer income.

Interest on private sector debt is considered to be a return for the service of private investors in providing productive capital to firms. But if the government builds up a power plant, the interest that is paid on this debt is counted as transfer payment and hence excluded form national income.

The reason is that interest is paid on such debt by imposing tax on others and not from the profit generated from the power plant. If government debt incurred in the past exists for a long time, the government will be making annual interest payments. But society’s product of goods and services is not affected by it or these payments are not associated with current output.

3. Valuation problems:

The valuation problem arises because some commodities are produced in the economy but are not purchased or sold through the market. Such non-market output cannot be valued at its market price.

The following two types of expenditure are valuation problems:

(a) Government non-marketed production:

A certain portion of output created by the government is not sold through the market. We can cite the example of education, defence, or fire service. Since there is no market price at which to value these goods and services, they are valued ‘at cost’.

The implication is that value of the output of such a service provided is taken as the cost incurred by the government in providing it. Thus, the government’s total production of goods and services is taken to be equal to the total of the government’s current expenditure.

(b) Stock adjustment:

The second valuation problem arises because stocks are often accumulated by the private sector. Since they are goods that have not been sold, they could be valued either at cost or at current market prices.

Valuation at cost means using the amount of money spent on them so far (net of the value of inputs purchased from other firms to avoid double counting). Valuation at market prices means valuing them at what they could be sold for today.

If the latter method is followed some profit margin will have to be added to cost to determine their selling price. In official national income statistics of most countries, market prices are used to value stocks. (However, accounting practices do vary from firm to firm).

Valuation of stocks at market prices has its own problems. In times of business recession, or a sudden fall in sales, stocks of unsold goods may rise. Because market prices are used to value stock, measured business profits will include the unrealized profits on these stocks.

This explains why the recorded level of profits in the national accounts is often very high even in a period of unexpected fall in sales. This often sounds like a paradox or creates confusion.

12. Omissions from Measured National Income:

Certain undesirable omissions often occur largely due to measurement problems and not due to methodological (conceptual) difficulties.

1. Illegal activities:

In measuring national income or output, we exclude all illegal transactions even though many such goods and services are sold on the market and generate factor incomes such as income from sale of drugs, or income from smuggling and black marketing. Such incomes are excluded because they are not reported to income tax authorities. So we do not have reliable information about these.

Similarly, a carpenter may do some work in one’s house and take payment in cash in order to avoid tax. As a result official figure of national income is a gross under-estimate of a country’s true national income. In a country where the volume of such transactions is very high we see the emergence of a parallel economy. The underground (or black) economy is often as strong as the official economy.

The rapid growth of the underground economy in most developing countries in the last two decades is largely attributable to income-tax evasion. It is also attributable to the faster growth of the service sector or the growing importance of services in the nation’s output.

A T.V. repairman or a window cleaner can easily pass unnoticed by the authorities than a large manufacturing establishment or a salaried person. It is also attributed to the fact that many people claim unemployment benefits while actually earning significant amount of income.

2. Non-marketed economic activities:

In a predominantly agricultural economy like our own farmers produce food mainly for themselves and their families. This is usual practice in subsistence farming, where farmers produce food for self-consumption and not for sale through the market. Or suppose you grow vegetables in your kitchen garden. If you sell a portion of it in the market due to some reason or the other, India’s NNP or national income will increase.

Non-market activities also include the services of housewives such as drawing water, or cooking or washing clothes, any do-it-yourself exercise, and voluntary work such as coaching or nursing or even canvassing for a political party.

In those cases where the value of non-marketed economic activities is very high official figure of NNP will significantly understate the real values of output and income earned. If we could measure the value of such consumption, we could include them in NNP.

The omissions of non-marketed economic activities become very serious when we try to compare the standards of living of different countries. In general the non-market sector of the economy is larger in rural than in urban areas and in less developing countries than in developed countries. For example India’s per capita income in 1994 was equal to U.S. $ 310.

It was not possible to live in the USA with that income. But one must not forget many of the things that are very costly to a US citizen are provided to an average Indian by a number of non-marketed goods and services.

We have noted that there are various measures of national income. These are different but no doubt interrelated. No one can be said to be the best for all purposes. In fact, each method bears relevance to a particular problem and serves a particular purpose.

The following points may be noted in this context:

Firstly, GDP provides the best answer to be question: What is the market value of goods and services produced for final demand: Moreover, for assessing a country’s potential military strength, we need to know (among other things) the maximum output (including goods) it is capable of producing.

Moreover, if we wish to assess the importance of a country as a market for our exports, we must look at its total sale and purchase figures.

It answers the question: ‘By how much does the economy’s production exceed the amount necessary to replace the capital equipment used up?’

3. Personal disposable income:

It answers the question: How much income do households have at their disposal to allocate between consumption and saving?

4. Real income:

Real (constant price) measures eliminate purely monetary changes and allow comparisons of purchasing power over time. Now answer the question: ‘With a rise of 10 per cent in the cost of living index, if a 20 per cent increase is allowed in the .wages by what per cent does the real wage increase? (Ans. By 100 per cent. Try to guess why.)

5. Per capita income:

It focuses attention on the average person rather than the nation as a whole. For studying change in living standards, we need per capita income figures.

To conclude with R.G. Lipsey and C. Harbury: “Economists and policy-markers who are interested in the ebb and flow of economic activity that passes through markets, and in the variations in employment opportunities for factors of production whose services are sold on markets, will continue to use GDP as the measure that comes closest to telling them what they need to know.”

13. National Income and Welfare:

Economists often raise the question: does an increase in national income lead to an increase in social welfare? Surely not.

The following points bear relevance in this context:

Firstly, many things contribute to social welfare but are not included in national income. An obvious example is leisure. If people in general enjoy more leisure NNP may fall, but people may feel happier than before.

2. Quality of Goods:

Secondly, the GNP may not adequately reflect changes in quality of products. A 1995 radio is a much superior product to a 1940 radio. It has better reception, and is more reliable and durable.

3. Different Levels of Consumer Satisfaction:

Thirdly, GNP fails to take note of the fact that different people derive different types of satisfaction from different goods, example, if the government increases its defence expenditure, GNP may increase, but may not raise welfare of the common people appreciably. On the other hand the same amount of expenditure incurred in hospitals or schools may produce great consumer satisfaction.

4. NEW and MEW:

National income, or more accurately per capita income, is used as an index of economic welfare. However, in recent years, recognition of shortcomings in national income accounts of various countries has prompted considerable interest in developing improved measures of output and economic welfare.

In this concept James Tobin and William Nordhaus of Yale University developed the concept of MEW in 1972. Arguing that the ultimate purpose of economic activity is consumption of production, they modify the currently used national income account data to provide an index called the measure of economic welfare (MEW).

In broad terms, to obtain MEW, GNP totals are adjusted by:

(1) Reclassification of expenditures into C. I. and intermediate production where only C contributes to economic welfare,

(2) Imputations of the value of sources of consumer capital, that of leisure, and the value of household work, and

(3) A negative correction for some of the disamenities of urbanisation. Samuelson calls it net economic welfare (NEW).

5. Illegal Activities:

Certain illegal and non- market activities add to people’s living standards but are not related to GNP.

Man does not live by bread alone’ like many other proverb have an element of truth. But it is nevertheless important to know how much bread one is having. Whatever may be the relation between national income and national welfare, there is no denying the fact that high levels, or fast growth rates, of national (per capita) income is needed for a better life.

Green Accounting:

It is interesting to note that from 1994 the US Commerce Department has augmented national ac : counts with the introduction of environmental accounts (also known as ‘green’ accounts), that are supposed to estimate the contribution of natural and environmental resources to the nation’s income.

The initial step in this exercise was the development of accounts to measure the contribution of subsoil assets like oil, gas or even coal.

The new national income estimates take into consideration the fact that discovery adds to USA’s measured reserves, while extraction subtracts or depletes the same. In truth, these two activities virtually cancelled each other out. So the net effect was negligible.

In the next stages, the Commerce Department is planning to investigate renewable resources like soils and forests and then to cover even environmental assets like air, water and wild animals. This new development is no doubt exciting. Developing countries may also carry out similar exercises by taking a leaf from the USA’s book.

So we have reviewed the measurement of national output from various angles and identified the short-comings of the GDP. Now our final question: What conclusion can we draw about the adequacy of a country’s national accounting system as a measure of economic welfare? Perhaps the best answer to this question can be given in the following words of Arthur Okun:

It should be no surprise that national prosperity does not guarantee a happy society, any more than personal prosperity ensures a happy family.

So growth of GDP can counter the tensions arising from an unpopular and unsuccessful war, a long overdue self-confrontation with conscience of racial injustice, a volcanic eruption of sexual mores, and an unprecedented assertion of independence by the young. Still, prosperity is a precondition for success in achieving many of our aspirations.

National income figures are used for various purposes.

The following points may be noted in this context:

(a) Economic Planning and Regulation of the Economy:

Although economic planning was feature of socialist economies such as that of the former USSR, now socialist countries as also mixed economies also control their economies. Consequently in such countries national income statistic provide a great deal of valuable information to both local and national governments.

The planning and decision-making authorities are able to interpret what is happening to investment outlay, consumers expenditure, public authorities spending, etc., and see which industries and regions are expanding or contracting.

The statistics published annually in India in the White Paper on National Income by C.S.O. (of the Planning Commission) play an important part in the determination of the Government’s economic policy. For example, the White Paper provides details of changes in three important variables, namely, saving, investment and consumption.

Saving represents the proportion of national income which is not spent on consumption goods and services. The economic importance of saving lies in its relationship to investment that is, the production of producer’s goods such as new factory buildings.

Saving is a necessary pre-requisite of investment. Consumption means the total output of consumer’s goods and services. Detailed information of these changes are essential for the formulation of any form of national economic planning.

(b) To Compare a Country’s Standard of Living Over Time:

It is normally assumed that when national income increases this is a good indicator because the standards of living within the country are supposed to improve as a result.

It may apparently seem that if national income rises, the standard of living of the people of the country must rise. If an individual’s income goes up, then the country is better off, i.e., the standard of living has improved.

However, certain qualifications have to be added to this view. The rise in national income may be due to price inflation. Even if there are real increases in the national income, there are still other factors to be borne in mind when interpreting the figures.

These include the following:

1. Population changes should also be brought into consideration. For example, if over a certain period the national income of a country rises by 25 per cent, but over the same period there is a 40 per cent increase in the population, can we say that living standards have gone up? If we wish to use national income statistics to find out something about the standard of living, the important figure in this respect is per capita income.

2. Rises in national income may be accompanied by effects which adversely influence the standard of living of the vast majority of the people. A rise in national income may be accompanied by an increase in the amount of pollution. This environmental damage may more than offset any advantageous effects of the rise in national income.

Moreover, it may be that the national income of a country has risen because people are being forced to work more hours. Is it then possible to say that the standard of living has risen, i.e., that the people are better off?

3. It is important to bear in mind the distribution of the national income. If there is an increase in national income, but all of this increase goes to only a few people, can we say that the standard of living in the country in general has risen? India’s Green Revolution, for instance, has benefitted the rich farmers and landlords.

A comparison based on per capita GN P is subject to the general limitations of arithmetic averages. For example, it reveals nothing about the distribution of goods and services.

A rise in the average figure per head does not show whether the increase has gone to a small number of very rich people, leaving the rest of the community in exactly the same position as before or whether the fruit of progress was shared equally by everyone.

In developing countries like India a figure for national income per head of the population will indicate little about the economic welfare of the people in general, because there are marked deviations from the average figure.

The rich, although relatively few in number, will pull up the average, but the poor, in much larger number, will be well below the average. Hence we must look at the trends in income distribution when using national income figures to assess living standards.

However in spite of these qualifications we cannot deny that national income per head figures still provide the best single indication available of changes in a country’s standard of living.

4. Fourthly, the per capita GNP figure tells us nothing about the composition of the goods and services available to the members of society.

For example, an increase in the Gross National Product may be due to a rise in spending on military equipment for defence purposes. Hence, while the statistics will suggest a rise in the standard of living, in fact, the extra production does not comprise goods and services which improve economic welfare.

Likewise, if the GNP figure rises due to a rise in the output of producer goods (machinery, factory building, etc.), the per capita figure will give an over-optimistic impression of the standard of living. It is the output of consumer goods and services that determines the current standard of living, although investment in producer goods permits a higher standard to be enjoyed in the future

(c) Comparison of Standards of Living in Different Countries:

Per capita GNP figures are often used to compare the standards of living in different countries. Thus if India’s national income is greater than that of Nigeria it is concluded that India has a higher standard of living. Such comparisons are useful for various purposes.

1. They provide an indicator of those countries which are in need of economic assistance.

2. They provide a basis of assessing each country’s financial contribution to international institutions. For example, the contribution of the United Kingdom to the European Economic Community budget was worked out in this way.

3. They provide estimates of the value of joining an alliance of other countries or of the strength of a potentially hostile nation.

(d) To Measure a Country’s Economic Growth:

Although economists are not unanimous about what constitutes economic growth, the most common measure is national income. Percentage growth rates are usually expressed in terms of percentage increases in GNP. Perhaps the best indicator of economic growth is real national income (per capita).

The term, economic growth, is generally taken to mean the annual per cent rate of increase of the real GNP, that is, the total annual value of home produced goods and services at constants prices.

When GDP is calculated a statistical correction has to be made to allow for changes in prices and in order to obtain the real rate of growth (of output). For example, if GDP increases by 25 per cent in money terms, the rise in real terms may be much smaller due to the effect of rising prices.